Exploring Our Industrial Heritage: Deadwood Goldrush

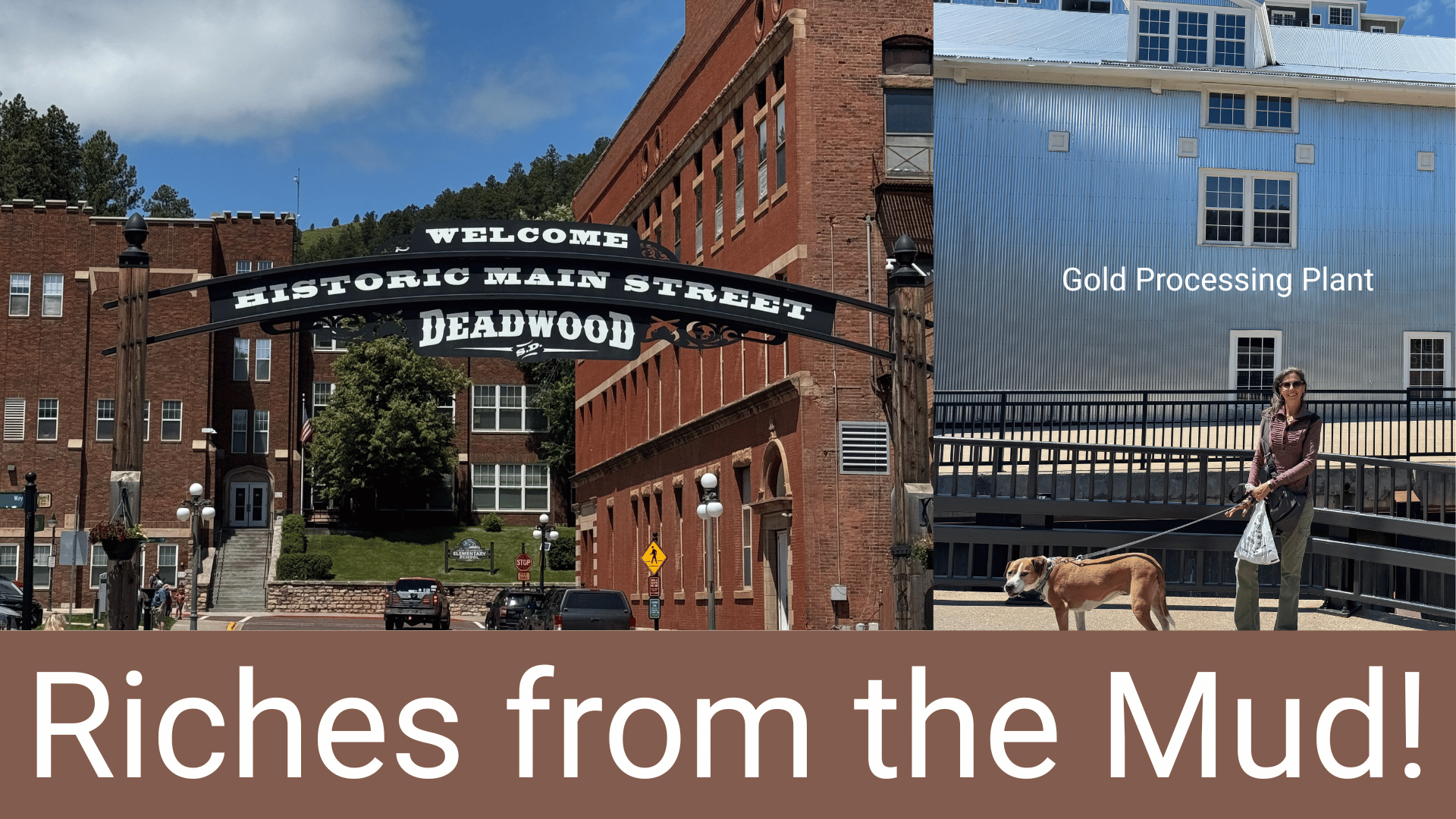

My wife Kelly, my dog Nala and I set out to explore our industrial heritage in Deadwood, South Dakota. There we found a rich deep history of the American west. The town of Deadwood was fun to explore with its stories of gunslingers and outlaws and its historic buildings and engaging old western vibe. This is where our exploration begins. Deadwood was a town born in a goldrush. The goldrush ushered in miners and salty characters from everywhere and an unlikely process engineer too.

When there is demand for a "thing" or "item", for a physical object, there is a manufacturing process that supports it. Minerals such as ore, nickel and yes, even gold require processes that convert them from ground minerals to usable forms. And this is where our story of Deadwood, SD begins.

A Goldrush

The Deadwood Gold Rush began in 1876 when gold was discovered in the Black Hills of South Dakota, drawing thousands of prospectors, fortune seekers, and outlaws to the region. Despite the land belonging to the Lakota Sioux under the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, miners poured in, sparking conflict and displacing Native communities. The boomtown of Deadwood quickly emerged, notorious for its lawlessness, saloons, and gambling halls.

Figures like Wild Bill Hickok and Calamity Jane became legendary in the town’s folklore, cementing its place in Wild West history. While few miners struck it rich, businesses supplying goods, services, and entertainment flourished. The gold rush transformed Deadwood into a lively frontier settlement, fueling economic growth but also leaving a legacy of broken treaties and cultural upheaval. Today, Deadwood embraces its gold rush heritage as a historic tourist destination, preserving the dramatic stories of its boomtown past.

A Process Improvement

In the 1800s, gold extraction began with placer mining, where prospectors panned river sediments or used sluice boxes to separate gold from gravel using water and gravity. As surface deposits dwindled, miners shifted to hydraulic mining, blasting hillsides with high-pressure water to wash gold-bearing soil into sluices. Eventually, hard-rock mining became common, requiring tunnels and shafts to extract ore from quartz veins. The crushed ore was then processed using stamp mills, which pulverized rock so the gold could be separated. Mercury was often used for amalgamation, though dangerous, to bind fine gold particles for collection and refining.

Innovations like Charles W. Merrill’s Merrill-Crowe process revolutionized recovery. This method, refining cyanide solutions with zinc, enabled efficient extraction from low-grade ores. While Deadwood’s early miners relied on crude techniques, Merrill’s advancements marked a turning point in gold processing, boosting global production and shaping modern mining practices.

Charles W. Merrill was an American metallurgist and mining engineer best known for his significant contributions to gold extraction methods in the early 20th century. Born in 1869, Merrill studied chemistry and engineering, later applying his expertise to improve gold recovery processes. He is most recognized for developing the Merrill-Crowe process, an advancement of the cyanide method used in gold mining. This technique involved clarifying and de-aerating the gold-cyanide solution before adding zinc dust to precipitate the gold, significantly improving recovery rates and making the process more efficient. The recovered material was refined into pure bullion. Cyanidation made it possible to extract gold from ore with as little as one part per million of gold, vastly expanding profitability and extending the life of many mines. However, the process introduced serious environmental and health risks, requiring careful management to prevent contamination of soil, water, and ecosystems.

Charles Merrill so strongly believed in his process that he asked for no compensation for his work. If he succeeded, he would be entitled to a share of the profits. His process focused on extraction of residual gold in sands and slimes from an existing Dakota processing plant. Merrill received a ten-year contract to perfect it and oversee the building and treatment plant. His work resulted in an increase in gold recoveries from 75% to 94%--and it made him rich.

A Hall of Famer

Merrill’s innovation transformed the mining industry by enabling the profitable treatment of low-grade ores, which had previously been uneconomical to process. His work contributed to expanding gold production worldwide, supporting both economic growth and industrial progress. Charles W. Merrill’s legacy remains influential in metallurgical engineering, where his process is still regarded as a cornerstone in modern gold extraction.

I had never considered that there is a National Mining Hall of Fame & Museum, Surprisingly enough, there is one and it is located in Leadville Colorado and Charles Washington Merrill is indeed an inductee.

What I realized during this step in my exploration of our industrial heritage is that when there is demand for a product, processes need to be invented and refined to optimize yield. These principles are the cornerstone of a continuous improvement philosophy. At the time in Deadwood SD, gold was the product and Charles W. Merrill was the process engineer who improved the process. A model of continuous improvement progress at its finest.

Stay connected with news and updates!

If you want some weekly T4T wisdom coming straight to your inbox for your reading pleasure - look no further! Join our mailing list to receive the latest blogs and updates.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.